So, this is a response to the responses to the

Aesthetics of Fat post, posted up front because, yes, it grew stupidly long. Again.

OK

Jonathan:

When you say that "fantasy" has no Modernist elements, that it could be classed a Romantic genre, and so on, this is precisely the reference slippage and aesthetic-form / marketing-category / commercially-branded-product error I'm talking about at the start of that post. It's a common error amongst SF-oriented readers to think fantasy = Fantasy = High Fantasy, but it's as baseless as the same category error applied to SF by those who, despite not reading it, are quite sure they know exactly what it is: science fiction (aesthetic form) = Science Fiction (marketing category) = Sci-Fi (commercially branded product).

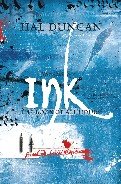

I could throw names of writers at you but I'll simply refer you to me own

Vellum here, which is consciously and deliberately constructed as a "Cubist" narrative. If I were to detail the Modernist elements in it we'd be here all day. You could, of course, turn around and say, "That's not

really fantasy. See the Modernist elements in it? Why that's patently SF!" I'm sure many do. My dad, meanwhile, would turn around and say, "That's not

really SF."

The desire for authenticity *is* a Modernist element, so saying it's not found in fantasy, that fantasy is a Romantic form is simply to narrow the definition of "fantasy" to include Romantic works and techniques but exclude Modernist techniqes. This is as bogus as narrowing the definition of SF to any one of the subsets of (combinable) modes at play in the field. For a pretty detailed breakdown of these modes as I see them, read the "SF as a Subset of SF" post, linked under "Scribblings on Scribbling" to the left there.

OK, so now apply that to "fantasy". Many of my playful variants of what "SF" stands for (So Fuck, Soul Fiction, Scientific Fancy, Symbolic Formulation) are equally applicable to works sold as "Fantasy" or identified as "fantasy". Fantasy is as much of a bastard hybrid as SF. Where does the desire for authenticity spring from? From the process of hybridisation, the interaction of Romantic, Rationalist and Modernist aesthetics in the diverse field of strange fiction we call "fantasy".

So rather than say...

Is this [aesthetic of authenticity] really a value of the genre...?... we should be asking: Which subset of the modes of (combinable) fiction that add up to what we call "fantasy" implement this aesthetic, and how does that affect our notion of fantasy as a "genre"?

My own notion of strange fiction is a sort of Grand Unified Field Theory of the works that we label SF, Fantasy, Horror, Slipstream, Magic Realism and so on. The full theory is laid out more fully in the posts linked (to the left again) as "Strange Fiction"; again it's pretty detailed and pretty damn long, but you might find it interesting if you've got a spare day or two :). The important point is that it provides (I think, anyway) a basis for addressing exactly the sort of issues you raise as regards authenticity.

Question:

[H]ow does the desire for a world to be geographically, socially and technologically authentic sit with the presence of magics and elves?Answer: Same way the desire for a world to be geographically, socially and technologically authentic sits with the presence of FTL and aliens. Elves, as a biological conceit, an invented species, are no more problematic than aliens (except in so far as they're presented as having magic powers). Magic is the big sticking point, but it's essentially just a metaphysical conceit, equivalent to the counterfactual and hypothetical conceits of Alt-History and SF. And such conceits are almost as notable in "SF" as they are in "Fantasy". FTL is actually a metaphysical conceit as much as magic is. The jaunting in Bester's

The Stars My Destination is even more of a blatant metaphysical. It is, to all intents and puposes, a conceit of teleportation as a magical ability to wish oneself from A to B.

It's only in Hard SF that metaphysicals sit uncomfortably with hypotheticals and counterfactuals. Which is to say it's only Hard SF writers and readers who make a clear-cut distinction between

acceptable hypotheticals and counterfactuals and

unacceptable metaphysicals. Note that many readers who reject strange fiction entirely consider the counterfactuals and hypotheticals equally ludicrous. They might well ask, with arched eyebrow:

...how does the desire for a world to be geographically, socially and technologically authentic sit with the presence of space travel and aliens?So, yes, we are talking about different sets of fans, but in adopting the strange fiction model, ditching the marketing tags of "Fantasy" and "Science Fiction" in favour of more precise modal differentiations, accepting that multiple modes are often implemented in any one work, we're able to look at the value of authenticity, for example, as a value of the

mode, and therefore as a value of the "genre" constructed from those modes.

Your third point is totally in tune with what I'm saying in terms of how some writers and readers question authenticity generated from explication. We could make a (subtle but relelvant) distinction between authenticity and the illusion of authenticity. As in SF where the scientifically savvy may differentiate between rigorous extrapolation and technobabble, so in Fantasy the historically savvy may differentiate between rigorous historification and specious windowdressing. Or may not.

The cardinal point I'm making is that while some (or much) of the "fantasy" we label "fat fantasy" can be considered as basically symbolic formulation, much of it will be better understood as, say, "Strictured Fantasy" or "Soul Fiction". Which is to say, it adds extra aesthetic values like authenticity, implementing another literary mode (explication versus excuse) in order to achieve this. Or it goes further in inverting the primary aesthetics partially or entirely, radically altering the modality. Some will maintain the primary aesthetics of accessibility, immersion and conventionality but place a complementary aesthetics of complexity, introspection and innovation (or subversion) into direct conflict with this. Some will perform a balancing act between the two sets of aesthetics, while some will capitalise on the tension between them.

In the context of this particular discussion, I'd say the notion of Strictured Fantasy is a good starting point for talking about Epic / High / Heroic Fantasy. What I'd seek to do is identify the aesthetic values inherent in

this mode that distinguish it from symbolic formulation. At a very basic level, I've tried to begin this by pointing to authenticity as an extra aesthetic value, an evident stricture that is foreign to symbolic formulation. I'd say the next step in the right direction might be

subversion. While the "cult of innovation" as Scott puts it, might have little effect on the aesthetic of -- let's invent another name, just for the fun of it -- Spectaculist Fantasy (much of it capitalises on conventionality, so full-on innovation would involve ditching a useful tool from the kit, so to speak), Scott's valuation of "subversion as subversion, fiction that is truly disturbing, thought-provoking, what have you, simply because of the kinds of readers it reaches" points to, I think, an aesthetic focused on reconfiguration of symbols and formula in subtle but highly pointed ways (i.e. keeping the tool of conventionality but using it in an unconventional way).

The aesthetic of Soul Fiction, I think, also offers scope for exploration. The resonance of the symbols we're dealing with in SF-as-Spectaculist-Fantasy, their archetypal effect opens up a whole new set of questions with regards to the psychology of immersion and identification. I don't think there's any question that much of the Monomythic import of this mode is geared towards consolation and compensation, but I also don't think there's any question that the collisions and collaborations of symbols of persona, id, self, anima/animus, shadow, ego and mana can serve more complex purposes such as individuation. Spectacularist Fantasy is psychodrama with the metaphors concretised. To a large extent I think the technique of exploitation comes into play here, with the incredible

not being resolved by explication or excuse, not completely at least. Many of Scott's "adventure junkies" are, I'd say, actually looking for an exploitative effect here, the unresolved incredibility being at the heart of the "fantastic" quality of the backdrop, the "kickass" quality of the characters, the "cool" quality of the storytelling -- the effect of psychodramatic rapture. The "high" of High Fantasy can be more, I think, than the "buzz" of symbolic formulation.

If I was to put a name to this as an aesthetic value I'd call it

articulation. This is where

complexity is valued in the experience of immersion and identification, where a work "speaks to" a reader because in articulating (combinatorially structuring) the symbols it articulates (expresses) relationships recognised by the reader as internal relationships between different resonant metaphors of identity, perhaps to the point of

rearticulating (combinatorially

restructuring) those internal relationships -- manifesting and resolving conflicts. The profound affect that results from effective articulation is part of what makes Spectaculist Fantasy so inspiring of loyalty. While sometimes, yes, the reiterations of the Monomyth can seem rather retarding, simply putting the reader through one Coming-of-Age after another, these are often the kind of books that readers consider life-changing. The book "spoke" to them at a particular point in life, articulated their identity to them in a way they might not have been able to themselves, and that experience was transformative.

Anyway, this is where the aesthetics of symbolic formulation becomes insufficient -- important, yes, but inadequate on its own -- as a toolkit for analysis of Spectaculist Fantasy.

Scott:

Maybe the above will give you a better idea of how I'm not trying to set up a distinction between types of readers that sets up one group as "getting it" while the others don't. But I'll try and lay out my intent more clearly.

I call those whose interests tend toward the exploration of soft-world alternatives, 'possibility junkies,' those whose interests tend toward character and narrative, 'adventure junkies,' and those whose interests tend toward hard-world alternatives, 'world junkies.'

I don't think our categorisations quite map. I'm not trying to distinguish readers here, nor even (strictly speaking) types of fiction (in the "groups of books" sense), so much as modes of writing and their relationship to variant and contradictory aesthetics applied by the writers and readers, any of which can be applied simultaneously in, or to, one work. I probably didn't foreground it enough in the post but as textual techniques exploitation, explication and excuse can be and are combined in (probably most) strange fiction. Many readers and writers like a bit of everything and apply multiple contradictory aesthetics at once.

Way I'd put it is we're all "incredibility junkies", getting off on the buzz of reading something that Could Not Possibly Be. Mostly, I reckon, we want adventure-in-a-world-of-(im)possibility. We want worlds and dreams built and broken and we want that process to consitute an adventure for us on whatever level. The three types of reader you're talking about should then theoretically be quite happy with reading the same story if it delivers on all three counts... and I think a lot of strange fiction aims to do exactly this. What I'm calling Spectaculist Fantasy above is a good example of this more rounded approach.

However I think it's evident that there are readers whose tastes are as much defined by a dislike of X as by a tendency of interests towards Y. If the aesthetics are contradictory that's to be expected, of course. You're going to get those who subscribe to one aesthetic absolutely and react against works based on conflicting aesthetics. For the purposes of the post, to explore the idea of an aesthetic based on accessibility, immersion and conventionality, I was focusing in on the extreme case of symbolic formulation, as the form where those values are adopted to the exclusion of -- or at least above -- all others.

The point being:

Where the [possibility junkies] tend to fetishize language's ability to defect from the real, and the [world junkies] tend to fetishize language's ability to replace the real, the adventure junkies simply like fantastic backdrops to their kickass characters and cool storytelling.

... but some are also deeply antagonistic to any defection from or replacement of reality which makes the story harder to parse. If they're real bona fide "junkies", that is. See, the "simply" is the keyword in that sentence. It's hiding a whole world of "merely" and "only" and "just", where that "simply" doesn't signify "this is all we require"; it signifies "this is all we accept". Because the adventure junkies of symbolic formulation can be seen as just as much fetishists.

Thing is, I doubt there's many of the other two types who dislike fantastic backdrops, kickass characters and cool storytelling, so that taxonomy as it stands is like a distinction between beef, pork and meat. Or, to bring it closer to home, Hard SF fans, High Fantasy fans and, well, readers who "just like a good story". When you say "fetishizing" that narrows the other two sets to readers who take a particular aesthetic (exploitative or explicatory) to its max, so defining adventure junkies in a wider sense is kinda like saying there's these two junkies and this, well, occasional dabbler in drugs. If we're going to talk about the other two type as narrow sets of "fetishists", shouldn't we be defining the adventure junkies as those who are fetishizing language's ability to X the real, whatever X may be?

Alternatively we could take the opposite approach. We could say that the "possibility junkies" simply like stories where language defects from the real, while the "world junkies" simply like stories where language replaces the real. This places their aesthetics on the same non-fetishistic -- i.e. non-extremist -- level as that of "adventure junkies". I think this is less useful though, largely because I'm more interested in the extreme cases here -- because I'm more interested in the aesthetics, and these become more clearly defined amongst the fetishizing readers. Still, that's actually what I'm building towards in terms of Spectaculist Fantasy, where exploitation and explication are not ruled out. Coming more from the "possibility junky" perspective myself, I'd describe my own aesthetic in a similarly non-exclusive way, as one where explication and excuse are not ruled out. I daresay there's many "world junkies" whose interest in explication doesn't rule out (i.e. over-ride completely) a liking for exploitative and excusatory modes and their results.

Anyway, to tweak your taxonomy a bit, if the first group maps to an aesthetic of exploitation, I'd tend to call them "

impossibility junkies". Where they're looking for language to "defect from the real", it's the non-possibility of the narrative that achieves this. The second group, in so far as they map to an aesthetic of explication, are so concerned with

restoring a sense of possibility they almost seem to better fit the first label. Way I see it, they're more about language's ability to

replicate the real; it's the simulation of reality they're seeking, versimilitude. The third group seem to me to be the ones who're actually concerned with language's ability to "replace the real" -- to substitute story for reality.

To me this sounds like a split into Modernist, Realist and Romantic aesthetics. You got (im)possibility junkies who are all about the defection from reality (c.f. Cubist fragmentation, Abstract non-representation, Surrealist symbolisation). Then you got world junkies who are all about the replication of reality (versimilitude, authenticity, representation). And you got adventure junkies who are all about the replacement of reality (with something bigger, better, bolder --

story). Given that we're talking about aesthetic forms of fiction that came together properly in the 20th Century, this tripartite distinction makes a lot of sense to me.

In those terms there probably is a fair mapping to my own model of exploitation, explication and excuse. But again, bear in mind that we're jumping whole levels to a high degree of abstraction and generalisation. What I'm talking about is textual techniques of dealing with the strange by flipping subjunctivity -- i.e. functioning on the sentence level. Factoring that up to the levels of story and aesthetic form, I see them as generally working together, except in

specific forms where the focus is largely or wholly on one as an application of a particular aesthetic. Factoring that up to a taxonomy of reader types

defined by one particular aesthetic... well, I'm willing to go with the idea, but only if we include a "none of the above" option or an ability to tick more than one box, cause I don't think all readers can be fitted neatly into those categories. As I say, we're all really incredibility junkies, far as I'm concerned.

I do, however, think you can factor those techniques up and get specific aesthetic forms with dedicated readerships, definable by their loyalty to one aesthetic over all others. I mean, I'm sure there are dyed-in-the-wool fans of symbolic formulation (and nothing but symbolic formulation). And this type of fan could be classified as an adventure junky if that's your preferred term. But I suspect what you mean by adventure junkies is readers primarily (or solely) interested in the heroic genres within strange fiction -- readers of Space Opera or Epic Fantasy -- rather than readers primarily (or solely) interested in the symbolic formulation sold within those genres. Which is to say, the adventure junky you're talking about is, I suspect, someone who's bringing an aesthetic based on more than accessibility, immersion and conventionality to the table. Something like I'm broaching in applying the values of subversion and articulation to Spectaculist Fantasy.

In practical terms, though, if we're talking

only about the aesthetics of symbolic formulation we're talking about a reader for whom "the interest in character and narrative" is entirely proscribed by accessibility and conventionality. This is the kind of reader, I'm arguing, for whom complex character and complex narrative equals "difficult" equals "impenetrable" equals "inaccessibile" equals

"no story". Which is simply to say, constructing a story from characters and narratives which are unconventional and / or complicated makes the story harder to parse, just as constructing a sentence from words and clauses which are unconventional and / or complicated makes the

sentence harder to parse. The aesthetic of accessibility is one which values the minimal complexity of an easily parseable story. Valuing simplicity in the construction of characters and narratives doesn't say much for one's interest in character and narrative as things in and of themselves.

However, as implied above, I

do think a lot of your "adventure junkies" value complexity in character and narrative; it's a requisite feature of subversion and articulation. A lot of them value complexity full stop. And even if some prefer a good solid riff to a twiddly-wank guitar solo in character or narrative terms, well, you can still do new and interesting things with just three chords. You can see the aesthetic of symbolic formulation coming into play though, where you run into hostility to this complexity: "Four chords?! None of that fucking prog shite, mate!"

To be frank, I think that aspect of hostility to complexity is not limited to symbolic formulation but can be found in all the genres that symbolic formulation subsists within. I have next to no time for it because it's generally phrased as an ignorant and arrogant refusal to recognise the very existence of a narrative in the face of complexity, or as a not-quite-so-ignorant but equally arrogant denial that the work in question is "proper" Fantasy or "proper" SF or "proper" whatever. And it pisses me the fuck off. It's the bleating idiocy of a moron who runs into a sentence with a semi-colon and a few polysyllabic words, and declares it to be nonsense.

That's by no means a characteristic I'm applying to all "adventure junkies" though. I know personally, from responses to Vellum, that many "adventure junkies" take complexity in their stride. They've written to say how much they enjoyed it simply on the level of kickass characters, fantastic backdrops and cool storytelling despite being utterly lost in terms of what story they're meant to be constructing. This makes me a very happy puppy, because I believe firmly that readers have a capacity to parse stories on an unconscious level, to make sense of them on a quite abstract level, so that they come out of a story thinking, "yes, that makes sense", even when they can't quite explain

how it made sense. I think these responses indicate that while they couldn't explain what the plot is, how it works, they were able to parse it satisfactorily in terms of situations, conflicts and resolution(s).

So...

Now on this scheme, if I understand you aright, the possibility junkies are really the only people who 'get it.' Having made a fetish of innovation, they dwell in the aporetic interstices between language's performative and representational functions. The world junkies, on the other, almost get it - they have an appreciation for the way language can perform realities, but in the end they go running back to the representational function, to the 'explicated world' as you call it - the fat. The poor adventure junkies, however, are left even further in the lurch, since they have no real appreciation for either function, and as a result are satisfied with hackneyed versions of the represented - fatuous fat.No, no, no, no, no! I don't even think in terms of a distinction between performative and representational functions. That sounds hideously pomo for my liking. I much prefer the old-fashioned breakdown of linguistic functions as referential, poetic, expressive, connative, phatic and such. And as for "aporetic interstices" and " the way language can perform realities"... to me that feels like looking at fiction on a level of abstraction which becomes metaphor more than anything. I am, I admit, quite interested in the way langage in fiction doesn't just perform a referential function but also poetic, expressive and connative functions, which -- if I read you right -- would be "performative" in opposition to "representational", but I'd argue that the aesthetic of Spectaculist Fantasy is as much concerned with these as my own brand of strange fiction. The expressive and connative functions in particular are, I think, particularly appreciated by adventure junkies.

I might well, partly from a personal appreciation of the poetic function, be a little judgemental when it comes to the type of adventure junky or world junky who rejects the poetic wholesale. I think having a "tin ear" for poetic features means missing out on a lot of the scope of strange fiction. But my real value-judgement is focused on those for whom the rejection becomes animosity rather than obliviousness, and it's largely reserved for those who go on to advocate the expunging of any poetic function in the name of accessibility, with or without the additional imperative of referential explanation to resolve the implausibility of the incredible.

This doesn't mean that I'm raising (im)possibility junkies over them as the ones that actually "get it", with "it" being a sort of all-encompassing "point of strangeness in strange fiction", a "what fantasy is all about". Rather I'm saying that within the diverse spectrum of incredibility junkies there are those who don't "get" the specific "it" of poetic function and for whom a resultant hostility-to-complexity becomes advocacy of a deeply limited and limiting view of what strange fiction can and should be. The point I was making in suggesting that, hey, if anything is to be called "real" fantasy maybe it should be the stuff that exploits the incredible -- that's meant to be read as a devil's advocate position. It's not a statement that only the exploitation purists are "right" in liking what they like; it's a usurpation of the concept of "proper fantasy" in an antitethetical stance, a turning of that prescriptivism back on itself. Were I facing up to the relevant analogue of an (im)possibility junky applying a similarly ignorant hostility, a pomo experimentalist prescriptivism which derided the referential function of language, say -- the literary equivalent of a Conceptual Artist dismissing figurative painting -- I'd adopt a quite different stance and it would be equally oppositional. Indeed, the whole point of my theorisation of strange fiction is largely to develop a vocabulary through which the incredibility junkies can reclaim the field as an innately diverse territory of aesthetic forms. One battle at a time, though. One battle at a time.

Now let me make clear here that I do not believe in posterity. Literature dies with our generation - I think that this is an incontrovertible fact. Technologically mediated social change, as drastic as it has been, is just beginning, and when it really gets rolling, our culture is going to need as much conceptual versatility as it can get. As a result, I think any writer who wants to make a positive difference needs to look at the apparatus of commercial publishing as an opportunity, and to adopt those forms that reach the most diverse readers possible. Those who don't simply aren't making a difference, aside from appeasing those who already share the bulk of their values - literally turning thoughtfulness into another socially inert consumer good.This is a social and political aesthetic of relevance and reach, of writing as a tool for social change. I may not entirely agree with the futurology of the prediction, and I'm not sure how you get from "the death of literature" to the "importance of commercial publishing" (unless by literature you mean not "writing" but "particular aesthetic forms of writing privileged by society with the term

literary"). But that's another discussion entirely. I do agree with the core aesthetic of relevance and reach.

So, when it comes to the "cult of innovation" and postmodernism, I think you're reading my priorities wrong. I'm far from postmodernist. Actually I've argued quite strongly on many occassions that postmodernism is a defensive reaction to a 20th Century backlash against Modernism, that in the wake of that backlash there was a wholesale retreat of those who couldn't take the heat into the safety of the ivory tower of irony, that the players left on the field, or those who came after, were forced to (or willingly and defiantly decided to) assume a marginalised position in the fields of genre and stand up to the onslaught of Contemporary Realism from there. The result, in both SF and Fantasy -- and I include Spectaculist Fantasy here -- was a vigorous hybrid of Romanticism, Rationalism and Modernism. The sensationalism of "novelty" and the intellectualism of pomo "cleverness" are both results of that hybridisation, and both, I agree, aesthetics to be wary of in so far as they push us away from relevance. Compare my critique of Populist and Elitist prescriptivisms and you should be able to see (I hope) that I'm no fan of either.

In terms of "performative tension" and "representational comfort", then, actually I see this as a false dichotomy which comes out of the pomo refusal of the integrity of the text. The sentences with which we construct strange fiction, as I see it, perform representation. It's a crucial feature of the generation of a subjunctivity of "this could not be happening" that there is a "this" being represented. The exploitation of that subjunctivity, the tension, is actually a feature of the

representation, of this imaginary construct of a thing which cannot be. The tension requires an acceptance that what is being performed is representation.

That division into performance and representation seems to me to come from the postmodernist refusal to accept the responsibilty inherent in a text as an act of representation. It's the quotation marks of irony, in which the text is to be understood not as true representation (which would imply import, which would imply intent, which would imply authority) but as an inherently artificial performance which represents nothing, as being said "only for effect". I deny the very possibilty of this. The quotation marks simply become a part of the text, so to speak, rendering the text a representation of performance. The text can never actually represent nothing and simply "be" the sum of its performative effects, not when the basic and fundamental effect is that of

representation.

I could go into this in more depth in terms of my own work as anti-pomo, as representing performance in a deliberate attempt to refuse the escape clause of "it's all just a game" (cop-out!), as using metafiction, for example,

not in an attempt to foreground the story as an artifice (cop-out! COP-OUT!) but rather in an attempt to immerse the reader in representations of representations of representations so as to blur the boundaries between their own reality and the representation of it, to make the representation more immediate and compelling. In many ways I want to steal the tools the postmodernists have been hogging and put them to good use where, I think, it matters, and metafiction's probably a good example of this. Breaking the fourth wall can be a way of distancing the reader from the representation, but I think it can also serve as a way of opening up the story so the reader gets dragged in, becoming utterly engulfed in the representation. And what rocks for me is that a lot of "adventure junkies" seem to have no problem whatsoever getting that; they really rather dig it.

In terms of that socio-political aesthetic of relevance and reach, my personal belief is also that epic fantasy is a great avenue for reaching a wide audience. Otherwise I wouldn't have written two stonking big fantasy books, the first of which verily shouts its adoption of the epic form in the opening lines. I just happen to be thrawn when it comes to limiting prescriptions of what you can and can't do in the form, so these epic fantasies

also happen to be Pop Modernist, Cubist Pulp, Indie Fiction -- pick your name. My own "manifesto" might also differ from yours in that personal history makes it very much about certain specific socio-political and psychological subjects for me rather than a wider struggle against cultural vacuity.

I'm happy to sacrifice accessibility -- which is to say, I'm happy to lose "adventure junkies" hostile to complexity -- if it means a novel that more profoundly articulates the emotional realities of, to put it bluntly, being queer and losing a brother, of isolation and the sort of grief that can hit you like a monster-truck, shattering your world and your very identity. I'm happy to sacrfice "accessibility" if it means more profoundly articulating that kind of reality to even

one single solitary reader somewhere who's dealing with that shit and for whom that articulation is helpful in making sense of it all. If that requires a complexity of fragmented character and narrative that renders it "inaccessible" to some who can't parse that kind of story and won't try, well, fuck 'em; I'm not going to compromise the work by offering a representational comfort that, in failing to represent honestly, ceases to provide true comfort. Hell, that part of my manifesto is stated about as clearly as it could be in Sonnet VII of my

Sonnets For Orpheus, in the whole "I sing for death..." proclamation. I make no bones about it.

So if I scorn symbolic formulation and its more outspoken champions it's because I reject their (frequent and loud) attempts to impose limitations on the aesthetics applicable in the field. For a writer like myself that hostility is a very real force that I can either submit to or stand up against. Submission would mean surrendering genre to that aesthetic, letting the philistines define the field in terms utterly opposed to the values I hold to most strongly. I'm not willing to do that, though it surprises me very little when writers are, given that they can publish in the mainstream, still have their work bought by the same huge market of incredibility junkies who would have bought it as genre, and add to that the huge market of readers hip to strange fiction but coming from an "indie" rather than commercial attitude. So, if I'm going to stick around in genre for the duration of a career rather than be the Next Evil Turncoat, I'm damn well going to hold my corner, stand up to that aesthetic of symbolic formulation, and call it as I see it -- an aesthetics of fat. Fat is tasty. Fat is not an evil scourge to be eradicated from the menu. I just don't see why we should let someone with a taste for fatty fat fat with fat on top dictate the menu.

All our grandiose proclamations about genre being where the action's at will become worthless bluster if we can't acknowledge that aesthetics of fat, analyse its effect on the field and

criticise it as Populist and philistine without being automatically assumed a paid-up member of the opposing camp of Elitist philosophers with their aesthetics of...what... celery, maybe? Frankly, I think the half-arsed critical vocabulary of "genre", where, over half a century since the emergence of the field, we still can barely distinguish a marketing category and an aesthetic form, is largely to blame for the incessant eruptions of snobbery and inverse snobbery that drive those divisions, the inferiority complexes and compensatory arrogance that lead us to deny the actualities of the aesthetics while simultaneously advocating them as absolutes. And I think those divisions are the

overwhelming reason why "genre" loses good writers to the "mainstream" where they can publish their strange fiction in peace without any of the bullshit about whether it's "proper" Fantasy or "proper" SF. As long as that process carries on, "genre" will become increasingly

less where the action's at and more where the action

could have been... if it wasn't for the philsophers and the philistines.